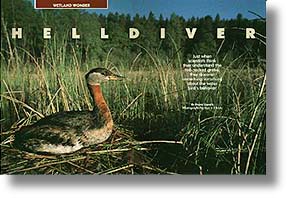

Helldiver

Just when scientists think they understand the red-necked grebe, they discover something surprising about the water bird's behavior

- Frank Kuznik

- Jun 01, 1999

"Ouch! Take it easy!"

"Ouch! Take it easy!"Bonnie Stout has her hands full. She's just snared a red-necked grebe, a tough, feisty bird that likes to make wildlife researchers pay for their curiosity. As Stout pulls the bird into her kayak and begins to untangle it from the net, it pecks at her hands and squawks in protest. It's still fussing a few minutes later, as the scientist gingerly prepares the bird for banding onshore.

"The trick with these guys is that if they can see you, they're going to fight," she says. "But if you cover their eyes, they'll quiet down."

"They usually leave Bonnie a present," adds Kyla Fennig, Stout's assistant.

"Yeah, they poop all over me," says Stout. "This one got it down my waders."

It's a small price to pay for an opportunity to learn more about the red-necked grebe, an elusive aquatic bird whose breeding and migratory habits are largely unknown. Though portions of the species' natural history, such as its mating rituals, are well documented, much of its life cycle is still a mystery. Even the red-necked grebe's population numbers and dispersal throughout North America are mostly guesswork at this point.

Those unsolved mysteries have driven Stout, a biologist pursuing graduate studies at Simon Fraser University, to a rugged patchwork of lakes and ponds in Canada's Northwest Territories where grebes gather to mate and raise their young in early summer. By banding the birds and then charting where and when--and with whom--they return every year, she hopes to answer some of the questions surrounding their movements and behavior.

"With marked individuals, we can study topics such as mate and site fidelity, and the question of whether pair bonds are formed at wintering sites or on the breeding grounds," says Stout. "We really have no information on what the young do in their first year or two. So anything we can learn by banding chicks will be valuable."

Such information is critical not only in compiling a body of knowledge about a species, but for understanding changes in its population and behavior. On Rush Lake in eastern Wisconsin, for example, the number of breeding pairs of red-necked grebes dropped precipitously (from 55 to 20) in the late 1980s. Whether that was purely circumstantial, or due to pollution, habitat loss or changes in climate or migratory patterns is an open question.

"Wisconsin is on the far eastern edge of red-necked grebes' range, so it may have been only a temporary nesting site," says Bruce Eichhorst, a University of North Dakota biologist who has studied bird populations on Rush Lake. "Or the loss of vegetation may have deprived them of nesting habitat." Without knowing whether individual birds return to Rush Lake year after year, researchers remain puzzled.

"Too often, we find ourselves trying to figure out what caused declines in an animal population that's no longer in its original, natural state," says Gary Nuechterlein, a North Dakota State University zoologist and specialist in grebe mating behavior. "That's the value of work like Bonnie's--getting the basic natural history, so if birds don't show up one day, we know what's going on."

Worldwide, there are 22 species of grebes, aquatic diving birds similar (though not related) to loons and auks. Seven, including the red-necked, are found in the United States. Also known as "helldivers," the birds are roughly the size of ducks, but share none of their affinity for flying, which grebes do clumsily and almost exclusively to migrate. With lobed feet on legs set far back on their bodies, grebes are built for swimming and diving.

The birds dive for food, snaring mostly fish or aquatic invertebrates. (In Stout's study area, leeches are a popular menu item.) They also dive to escape detection, disappearing with barely a ripple and resurfacing hundreds of feet away. If a grebe has established its territory, it will even dive to drive off an interloper, "submarining" the unwary invader with a sharp, unexpected poke from below.

During the summer breeding season, red-necked grebes range from Alaska down through the western Canadian provinces into the northern tier of states. They winter on both coasts. Scientists believe, though have not yet proven, that there are two distinct populations of red-necked grebes, which overlap during the summer but go their separate ways in the winter.

"It's sad but true that some of our best current information about how the population splits is based on contaminant levels in eggs," notes Stout. Analyses of grebe eggs across the prairie provinces of Canada have shown levels of PCB, DDE and other toxic substances consistent with those found in fish-eating birds on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. One study of grebe eggs in southern Manitoba found a contaminant specific to Lake Ontario, a likely indication that the eggs were laid by females who spent time there.

Red-necked grebes tend to dominate their nesting sites, laying claim to a pond or corner of a lake, then chasing away other grebes and waterfowl with loud calls and aggressive attacks. The birds practice an elaborate courtship and mating ritual, performing a precise series of postures and calls that culminate in copulation on a floating platform built by the pair. That platform becomes the nest site for a clutch of four to five eggs, on average. Male and female red-necked grebes share nest-building, incubation and chick-rearing chores.

Should a nest be plundered or destroyed, the birds will renest as many as five times. The nesting site is attached to floating vegetation close enough to shore to provide shelter from wind and waves, but out far enough to maintain swimming access to food and to afford some protection to young from predators. Eggs and chicks provide prey for raccoons, skunks, owls and other creatures.

Stout became fascinated with red-necked grebes in the fall of 1991, when she was counting migratory waterfowl at the Whitefish Point Bird Observatory on Lake Superior in upper Michigan. Until 1989, when the researchers there began conducting fall water bird counts, red-necked grebes were known only as nocturnal migrants; they were rarely seen in flight. But Stout watched as thousands of them passed over the area during the day, their distinctive flight profile hypnotic in such profusion.

"We didn't know of this migratory pattern until we started looking for it," she says. "I became obsessed with wanting to know where they go next. We know they end up at the ocean, but have no idea how they get from Lake Superior to the coast, where they don't show up for another month or two."

Stout searched the Great Lakes and found about 3,000 red-necked grebes molting in northern Lake Huron, which still leaves some 15,000 of the birds she saw unaccounted for. Molting sites are a key missing piece in the grebe puzzle, as the birds lose all of their flight feathers at once, leaving them vulnerable for several weeks to whatever contaminants are in the water and food where they land.

"If something goes wrong on one of those molting lakes, it can be a major disaster," says Nuechterlein. In 1992, an estimated 150,000 smaller and more common eared grebes died on an inland lake in California that apparently had been contaminated by industrial runoff.

To research breeding behavior, Stout moved her study site to a forested region in the Northwest Territories, near the capital city of Yellowknife, where she found easy access to several lakes and ponds that provide nesting habitat for grebes. Still, she discovered, banding the birds was not easy work.

Though just 300 miles south of the Arctic Circle, Yellowknife can be hot and dusty during the summer, and the woods harbor swarms of mosquitoes and blackflies capable of working their way through even serious bug gear. "I was so bitten up at one point, I looked like I had smallpox," says Stout.

Working in a large study area means spending much of the day bouncing in a pickup along dirt roads, then stopping at ponds to conduct the tedious search for birds through scratchy marsh grass and fireweed. When Stout and Fennig spot an accessible pair of grebes, they haul their kayak to the pond and Stout paddles to a strategic point, spreading a floating gill net 50 feet long and 8 feet deep. Sometimes they play a tape of grebe calls to decoy the birds into the net, a tactic that works particularly well early in the breeding season when territories are still in dispute. Later, Stout tries to "herd" the birds into the net, a hit-and-miss technique that generally fools one grebe, but makes the other wary.

"They're quite clever birds," says Stout. "Once they know where a net is, they'll avoid it. And we don't want to bother them too long." Rather than harass the grebes, or risk overheating the one waiting on shore while trying to capture its mate, Stout will settle for banding "half pairs."

While attaching leg bands, the researchers handle a bird as gently as possible. Loose feathers are saved for DNA analysis, and the grebes are weighed and measured before being returned to the water. Moments later, the birds are calm and apparently no worse for the wear, though as Stout notes, "Next time I pull up in that green truck, they'll hide a lot quicker."

Banding grebes becomes problematic as the summer wears on, partly because the ponds become choked with vegetation, but largely because the birds can't be disturbed once the chicks have hatched. Chicks initially ride around on an adult's back, staying safe from predators, while the other adult fetches food.

Within two weeks of hatching, the chicks can swim on their own. The adult grebes at Stout's study site often divide care of the brood, sometimes exclusively feeding and minding "favored" chicks while ignoring the others, to the point of chasing them away. While such behavior seems cruel in human terms, in the long run this practice probably increases the chicks' chances of survival.

"The parents can often fledge more young if they each take part of the brood," explains Nuechterlein. The chicks tend to set up their own hierarchy with infighting, and the dominant one gets the most food. "If you split them, two parents are diving, each feeding half the chicks, which is a more efficient way to raise the young."

When the chicks are 5 to 8 weeks old, one of the adults may abruptly leave the area. "It may be that the food supply in the pond is getting low, so that gives the remaining birds more to eat," says Stout. "My pet theory is that it's tied into molt schedules. But those are just guesses--we really don't know."

Nor is there any guarantee that red-necked grebes nesting in other regions act in the same fashion. "One thing you come to realize about grebes is that you're never an expert," says Nuechterlein, who has been studying the birds for 24 years. "Some things, like the courtship rituals, may be largely determined genetically. But other behavior is very malleable, and can be totally different on different lakes. That's what makes them so interesting."

Indeed, an encounter with red-necked grebes invariably raises more questions than it answers. How do chicks know, for example, where to migrate after their parents are gone? And why do certain behaviors vary so widely?

Bit by bit, the work being done by Stout, Nuechterlein and others will answer those questions about red-necked grebes. For now, though, many of the mysteries surrounding these remarkable diving birds will continue to linger.

Ohio writer Frank Kuznik visited with grebe researchers in Canada's Northwest Territories for this article.